Pamplona, Spain – November 14th, 2010

Since arriving in Spain, I’ve seen the simple but striking outline of a black bull emblazoned on t-shirts, keychains, and bumper stickers. It seems to be every bit as strong a national symbol as the Spanish flag itself – in fact, the two are often combined, especially for sporting events!

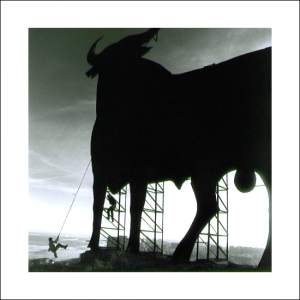

There are also postcards sold here and there which appear to show a large, standing interpretation of the black bull in a field of sunflowers. Later, I was out with some friends when we spotted one by the road. It was enormous – a thin piece of metal painted jet black and standing proudly over the highway. I was starting to get curious. This was clearly a different specimen than I had seen in the postcards, and, now that I thought about it, I’d seen another one in my friend’s photographs from the Canary Islands. So there were at least three across Spain, I thought, and logic would say there were likely to be more… a good deal more.

I’ve kept my eye out on my travels around Spain, and by now I’ve probably seen close to a dozen, perched everywhere from the dry, rocky roadsides of Alicante to the lush green hills of Galicia. My curiosity was piqued. How many were there? How did they get where they were? How are they maintained? I assumed that they had been placed along the highways in order to reflect a national symbol – but after a little bit of research, I learned that the truth was precisely the opposite, and that the bulls have a long and complicated history that has taken turns no one could have predicted.

———————————————————-

The History of the Osborne Bulls:

It all started in the 1950′s, when the sherry company Osborne (incidentally, the second oldest company in Spain), chose a simple bull logo to advertise their new brandy, and began erecting modestly sized wooden billboards in the shape of this logo, each painted with the word “Osborne”. If these bulls sound quite different from those seen today, that’s because they were!

There were once more than a hundred 'bulls' across Spain, each held together with more than 1,000 bolts.

Soon, weather conditions required the company to switch their material from wood to metal, and they increased the size of the billboards to 7 meters. Then, in 1962, new laws required advertisements to be kept further from the roads, so the size of the bulls was double to a massive 14 meters, and they were strategically placed over flat stretches or on hilltops in order to maximize visibility.

Advertising restrictions continued to tighten, and by the late 1980′s Osborne had to remove their names from the sign and paint them plain black in order to follow regulations. This worked for a few years, until new laws said that the bulls – plain black or no – would have to be taken down.

Then, something extraordinary happened – the media and the people of Spain leapt to the billboards’ defense – a massive ‘save the bulls’ campaign was initiated. The argument went all the way to Spain’s Supreme Court, which in 1997 ruled that the bulls had transcended mere advertising icons, and were now part of Spain’s cultural identity and heritage.

The bulls were safe! Well, mostly. Some had already been destroyed before they were given protected status, and those that remain are still subject to the weather (in 2009, one of the Alicante bulls was demolished by strong winds – it has since been rebuilt) and vandalism (the only bull in Catalonia, near Barcelona, has been repeatedly vandalized by Catalan nationalists, and has not been rebuilt after its most recent destruction.)

The Osborne company itself has had mixed feelings about the bull saga. Just as the status of the bulls as cultural icons has protected them from advertising regulations, it has protected manufacturers of souvenirs utilizing the logo from copyright restrictions.

——————————————

Where are they now?

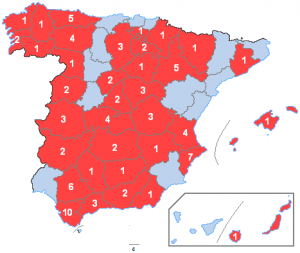

The 89 remaining Osburne Bulls are scattered unevenly across Spain, from the greatest concentration (23) in Andalucia, to the single speciments of the Basque Country, Navarra, Catalunya, the Balearic Islands, and the Canary Islands.

For fellow residents of Navarra, ours is in the south, near Tudela.

Wherever they are located, the bulls are taken care of today by Felix Tejada and his family, in whose workshop they were first created.